What The Hell Are You Talking About?

what’s distinctive about your subject and why that (really) matters

What the hell are you talking about?

You know what it feels like to think this. You might know what it feels like to say it. You may even know what it feels like to have someone say it to you, brows furrowed in frustration.

It’s confusing, sometimes infuriating, to have someone tell you something without making it clear what they’re talking about. Identifying the subject of a communication matters, and it matters even more when it’s not a conversation, but a book.

Books, after all, are not a two-way conversation and don’t happen in real time. The reader can’t ask for clarification, they can only read what’s been written down. It is the responsibility of the writer to make sure that what’s been written down includes the information a reader will need to understand whatever the writer has to say. This begins with the subject.

Subject is such an important component of books, in fact, that it’s how we usually organize them. Wander into your local indie bookstore and you’ll see the evidence on the shelves in the form of signs that say things like “biography,” “travel,” and “mystery fiction.” A book’s genre, in other words, is connected to its subject: the “biography” section consists of books whose subject is a given person’s life, and the “mystery fiction” shelves hold books of fictional narratives whose subject is solving crimes.

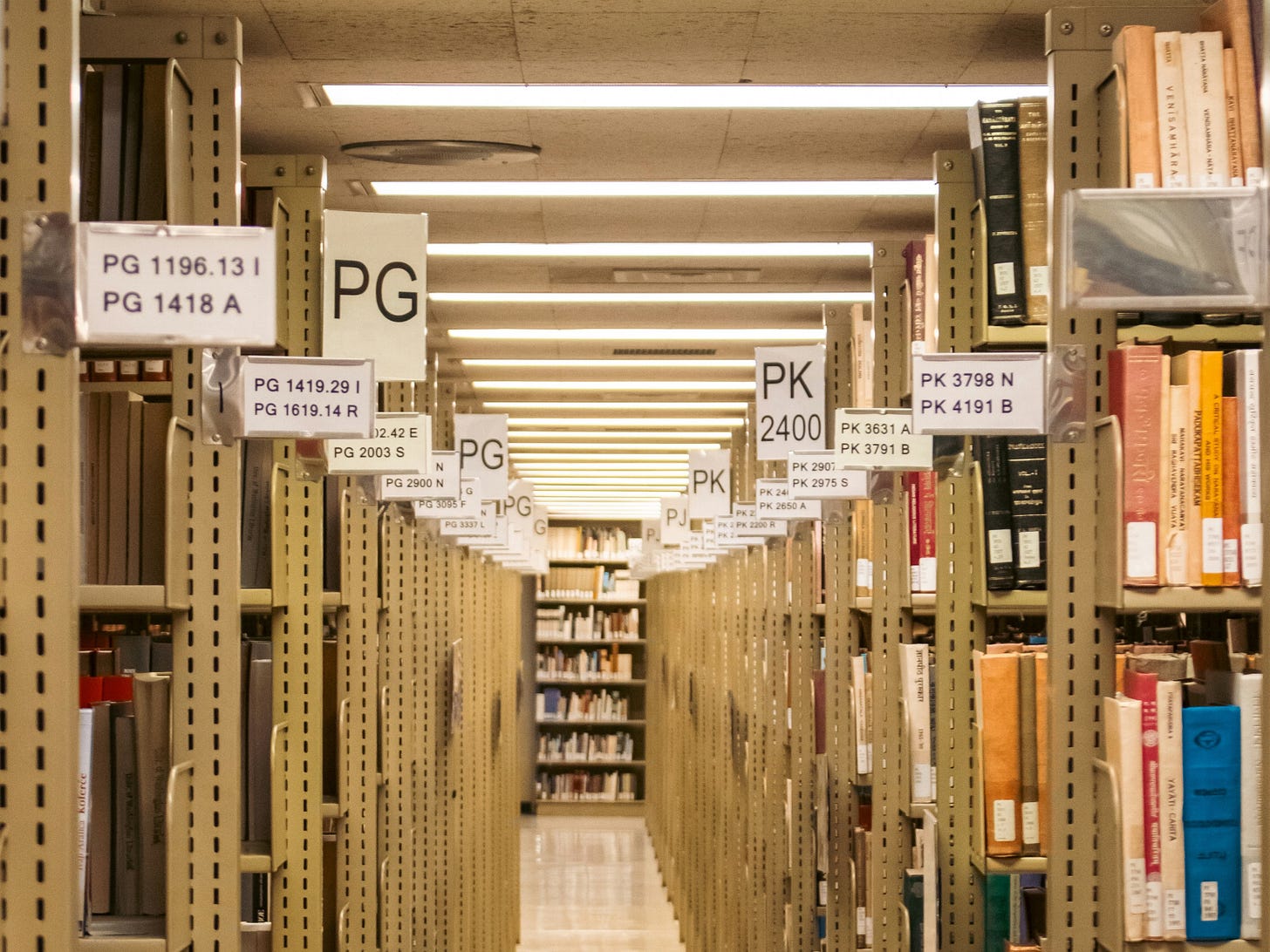

In libraries, the connection between subject and organization is even more direct. Library classification systems like the Library of Congress numbering system and the Dewey Decimal System are arranged by subject, so much so that librarians, academics, and other people who spend a lot of time in libraries become fluent in the language of those subject-specifying call numbers. Some of my college friends belonged to the “HQ76 Club,” a group for LGBTQ librarians named after the Library of Congress classification number for books about homosexuality.

Subject is such an important component of books, in fact, that it’s how we usually organize them.

When we organize books by subject, readers can easily locate a book on the subject they want to read about. Organize them any other way, for instance alphabetically by the author’s last name, and you’ll end up with a book about bicycles, a thriller set in Patagonia, and a Thai cookbook one after the other. Fun to browse, maybe, but horribly inefficient if you want to read about something in particular.

Because we do organize books by subject, it becomes crucial not only to be clear about what a book’s general subject might be—what Library of Congress number it’d be shelved under—but also to be clear about what makes a specific book’s take on that subject distinctive. Readers don’t simply walk up to the “travel” shelves and pick one at random. Typically they don’t even walk up to the “travel” shelves, go to the “Latin America” category, and then pick one at random. They go to the general subject category and then they drill down, looking at titles, flap copy, and tables of contents until they find that book on historical walking tours in Lima that speaks to their interests.

What’s distinctive about your version of your subject is what makes it stand out from everything else on the topic.

What’s distinctive about your version of your subject is what makes it stand out from everything else on the topic. Being able to clearly identify what’s distinctive about your subject, in as few words as possible, will not only help readers find their way to your book. It also:

establishes your book’s relevance: how is this book different from others in the same general topic area?

legitimizes your book’s presence among its peers: what does this book offer that isn't in all the rest?

focuses your attention on what’s special about your project: what’s valuable about what I am bringing to the reader?

When you can identify what’s distinctive about your version of your subject, you are automatically equipped to make a better case for your book. Finding an agent, editor, or publisher is rarely a simple process, but the more able you are to make a strong, concise, direct, clear case for your book, the smoother it tends to go.

The same ability is worth a lot when you are marketing a book to readers, appearing on podcasts, and any other time it’s to your advantage to give someone a gorgeous little snapshot of why your book is the one they want to read next.

Most importantly, defining your distinctive subject focuses you and your understanding of your book. This makes it easier to conceptualize, structure, and write.

…defining your distinctive subject focuses you and your understanding of your book.

Ask yourself "what am I doing differently with this subject? Within the big “library shelf” arena of the subject, which bit is my turf? What’s distinctive about that?"

Another way to do this is to ask "of all the possible things within this big subject area, what am I not writing about?" Knowing what you aren’t trying to do can be downright liberating: phew, don’t have to worry about that part.

A distinctive subject is relevant to almost every book, whether fiction or nonfiction. What is it that gives your supernatural horror novel its special twist, or makes your book about child development different than that one over there? Unless you are writing the very first book ever to deal with a particular subject—I’ve done this twice so far, personally, but on the whole it’s pretty rare—there must be something about your approach or take on your subject that makes it particular, specific, and special.

As a writer, you never ever want a reader to furrow their brow at your book thinking “what the hell are you talking about?”

The beautiful thing is that you can tell them.

— Hanne Blank Boyd

p.s. If you’re not ready to subscribe, leave something in the Developmental Edits tip jar.